We found ourselves always asking the same questions. If a client stops sending us this API field, what ML features will be affected? Does this feature use this part of the code? What features depend on this service? We put together the dream hackathon team to build a chatbot to answer these questions for us.

Traditional RAG systems

Let’s focus on the question of “what ML features depend on X”.

Like me, your first instinct might be to use VSCode’s search box to see where a variable is used. But Go codebase is very complex, and this approach leads to endless clicking following diverging trails between variables and functions. You end up overwhelmed and not really understanding the dependencies between separate parts of the codebase.

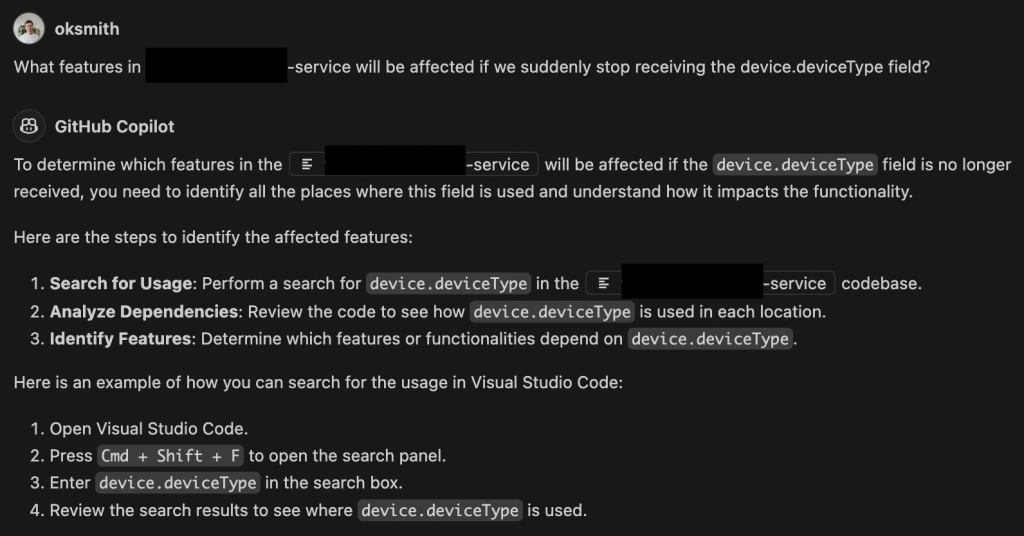

Your second instinct might be to use Copilot. I tried that too, but it told me it couldn’t answer the question and suggested a brute force search like the one I outlined above!

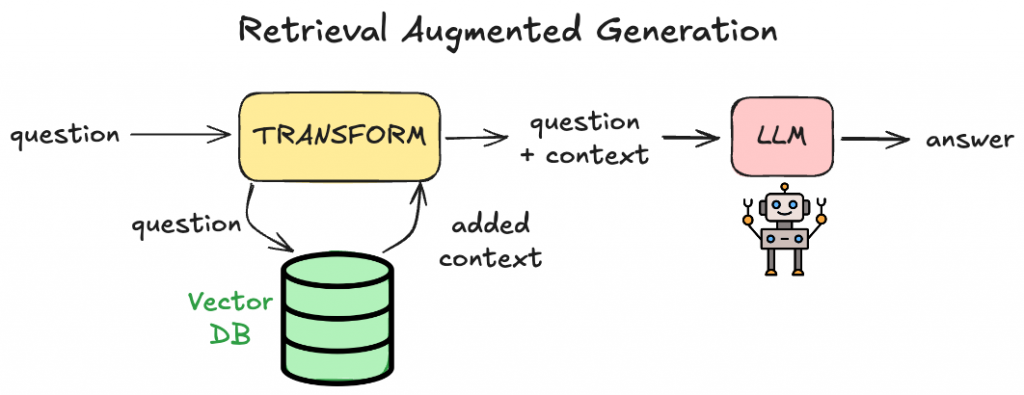

Chatbots like this use RAG (retrieval-augmented generation) – it’s a widely known way to feed the LLM domain knowledge that it wouldn’t have been trained on. It’s a way to reduce hallucinations, and allows you to verify the answers yourself (since you can also return source information e.g. URLs that were used to generate the answer!).

RAG systems work by embedding the semantic meaning behind each document into a vector store that you can query against from. When a user asks a query ![]() the system embeds

the system embeds ![]() into a vector, performs a similarity search to retrieve the top

into a vector, performs a similarity search to retrieve the top ![]() matching vectors, decodes them back into the original text, and adds this context to the original question as additional context. This combined input is sent to an LLM, enabling it to provide more accurate answers.

matching vectors, decodes them back into the original text, and adds this context to the original question as additional context. This combined input is sent to an LLM, enabling it to provide more accurate answers.

Copilot is a sophisticated RAG system. But, as with many similarity-based RAG systems, it struggles to answer complex questions requiring knowledge across the entire repository structure and dependencies. These repository-level questions are often what we really care about. So vector similarity-based RAG is simply not enough.

Building the graph retrieval chatbot

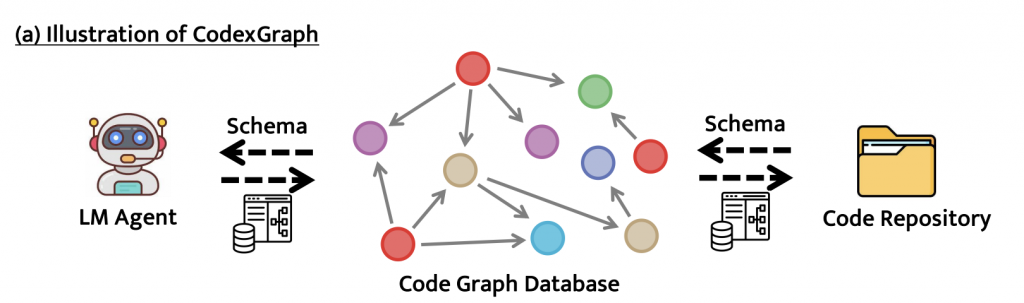

When we were building our application we found CodexGraph [1], which is very similar in spirit to what we wanted to achieve. However, it wasn’t right for us, because (a) it only works on Python repositories, whereas we wanted to use it for Go code (b) its LLM config only contained OpenAI models, whereas we wanted to use local LLMs (or Gemini, as I’ll talk about later). But I highly recommend reading that paper because it outlines some very core ideas nicely.

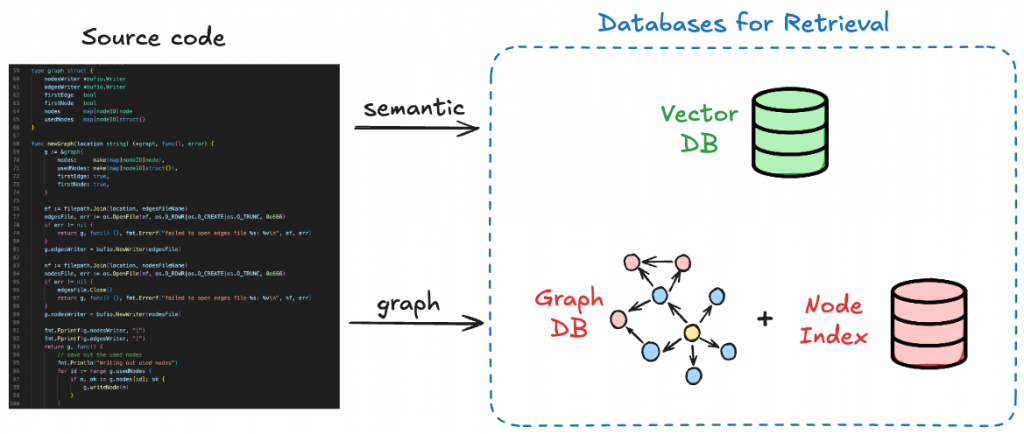

Step 1: Extracting the Graph

Our Go code contains very subtle and complex relationships. A feature might be the result of: extracting several different entities from the request, fetching data via an RPC call to one or more completely different services, looking back at the customer’s historic data we’ve cached, and more. This means code analysis tools need to jump over some pretty complicated hurdles to achieve the right answer.

Creating our own Go code parsing tool meant that we had a lot more flexibility in how we constructed the nodes and their relationships. We used the Go ast package to extract this information.

We decided to track the flow of data throughout the codebase, where nodes can be things like variables, struct fields and functions. And edges can be things like variable assignment, function calls, and functions returning variables. It turned out to be a very hard, fiddly problem to solve in a precise way.

Through trial and error, (and patience, and pain) we produced a graph with ~400k nodes and ~600k edges representing the flow of data from one variable to another, using only a subset of our codebase. It has been designed in a way such that extending it to include new edge types and node types to address potential gaps is relatively easy. The end result was a JSON file containing the nodes and their properties, and a JSON file containing edges.

Step 2: Creating the Graph Database and Node Index

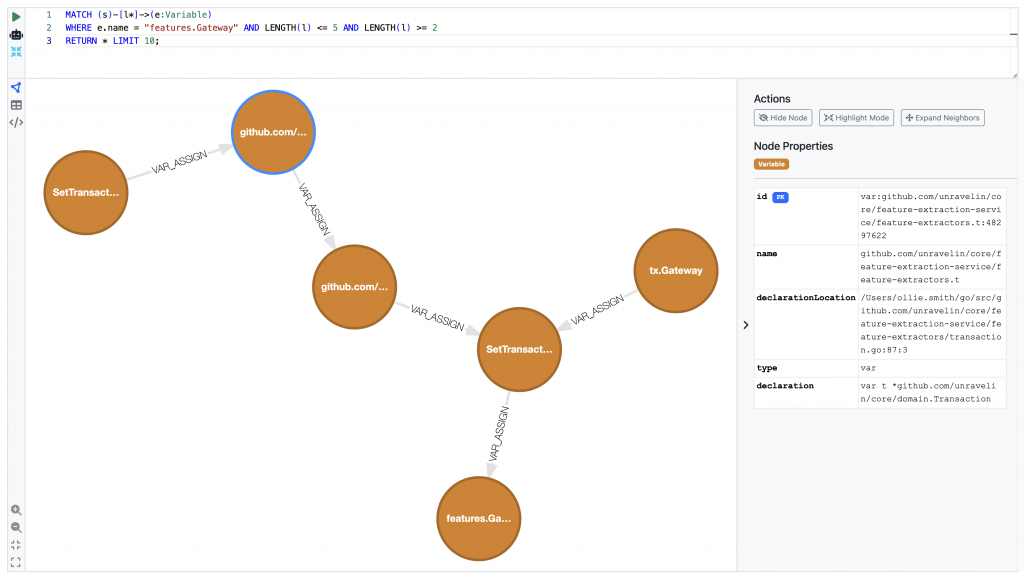

For the graph database tool, we decided to use Kùzu. It’s an open source, embedded database which is designed for efficient analytical graph queries. We chose to use Kuzu as our graph DB (as opposed to, say, Neo4j) because latency and transactional queries aren’t our main concern. We don’t need an external server, in fact we preferred to keep all data within the realm of Ravelin for this project. It also uses Cypher as its query language, which means that much of the documentation for writing Neo4j Cypher queries also apply to Kuzu.

Setting up a Kuzu database is simple as creating a database connection and copying the data across from JSON files:

Once you’ve created the database, you can inspect it by running the Kuzu explorer. It’s a built-in tool allowing you to execute Cypher queries and visualise the outputs! You just need to pull the Docker image and it should work. It has an intuitive drag-drop interface and can be a nice way to debug things.

The final part of building the graph, was to create a node index. This is because many graph retrieval mechanisms needed for graph RAG need to have a “starting point”. The node index is created by embedding each node’s associated test (and/or metadata) into a vector space using an embedding model. These embeddings capture the semantic meaning of the node’s information, allowing you to query into it based on an unseen user question. But more on that in Step 4!

Step 3: Building the Semantic retriever

We first took our repository and split it using LangChain’s programming-language-aware splitters to chunk the files up into smaller documents. These documents were passed into an embedding model and saved in a vector store.

Next is to choose an embedding model to use to transform the text chunks into a bunch of numeric vectors. The great thing is that this can be entirely decoupled from the choice of LLM in the chatbot; in fact the best embedding model to use is the one that’s best suited for your application. In our case, we looked at embedding models which are designed to provide efficient representations for codebase Q&A tasks.

We chose Chroma for our vector store, because it supports persisting the database to local disk. This was nice, because it’s in line with our vision of “keep everything local!“, since them we didn’t need to worry about storing sensitive code with a third party vendor. However, if you’re looking for lightning-fast application then Chrome might not be the best, and you might prefer Pinecone or Faiss (the latter is also open sourced).

Once you have yourself a vectorstore containing your embedded codebase, you can perform a cosine similarity search and select the top ![]() most similar documents, and use those as context. This is our semantic retriever. It’s very efficient at understanding the body of the functions and how they work in detail which can help for particular types of user questioning.

most similar documents, and use those as context. This is our semantic retriever. It’s very efficient at understanding the body of the functions and how they work in detail which can help for particular types of user questioning.

Step 4: Building the Graph retriever

The graph retriever combines the output of Step 2 with some of the ideas in a traditional retriever (Step 3).

There are different ways you can retrieve documents from a graph. LlamaIndex supports a few:

- VectorContextRetriever – this is selecting nodes and their metadata from your node index, much in the same way you would a semantic vector search.

- CypherTemplateRetriever – use a cypher template with parameters which are inferred by an LLM. This retriever makes use of specifically templated queries you define ahead of time, and you ask the LLM to extract relevant entities from the user question to fit the query template.

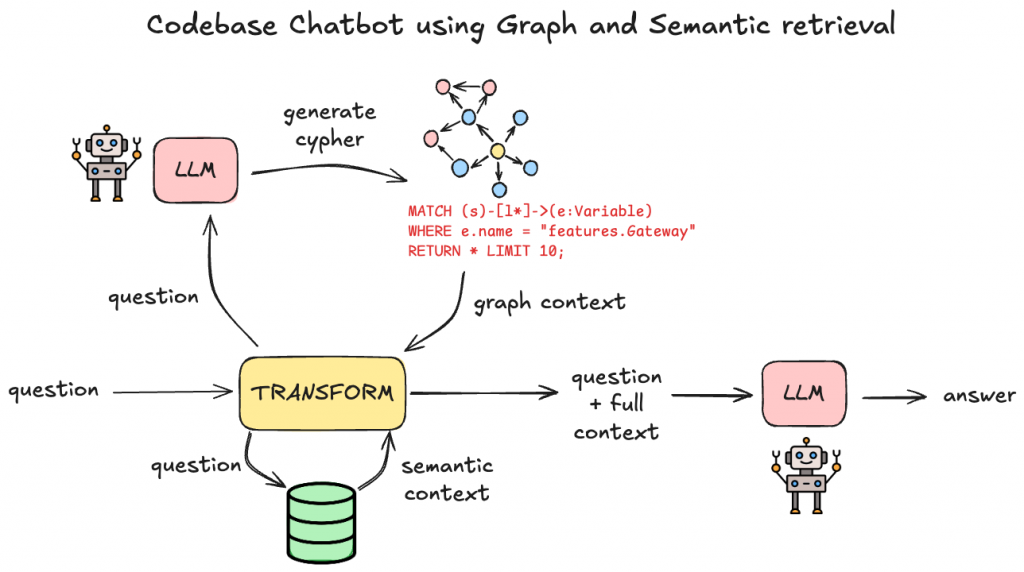

- Text2CypherRetriever – this is where you ask the LLM to generate the entire cypher query based on the schema of the property graph and what the user’s question is. The output of the cypher query might be nodes or edges and their metadata which can be used as context to answer the question.

We started our project by using cypher templates, but we found that giving the LLM a clear schema of our Kuzu database and some hints of what we’re looking for with some few-shot learning, we were able to use Text2Cypher to great effect. This way we cover a much larger space of graph-traversal queries that we might not have thought of adding to a template.

Our actual graph retrieval contains some try-except blocks so that, if the Cypher query that’s generated by the LLM does fail for whatever reason, we still have reasonable fallbacks that can be used to provide graph context.

Step 5: Assembly!

Combining it all together, the flow from user question to final answer from the LLM looks like this:

The main LLM we used for this project was Gemini. We tried some local LLMs such as Llama 3 but we found that Gemini produced the best results.

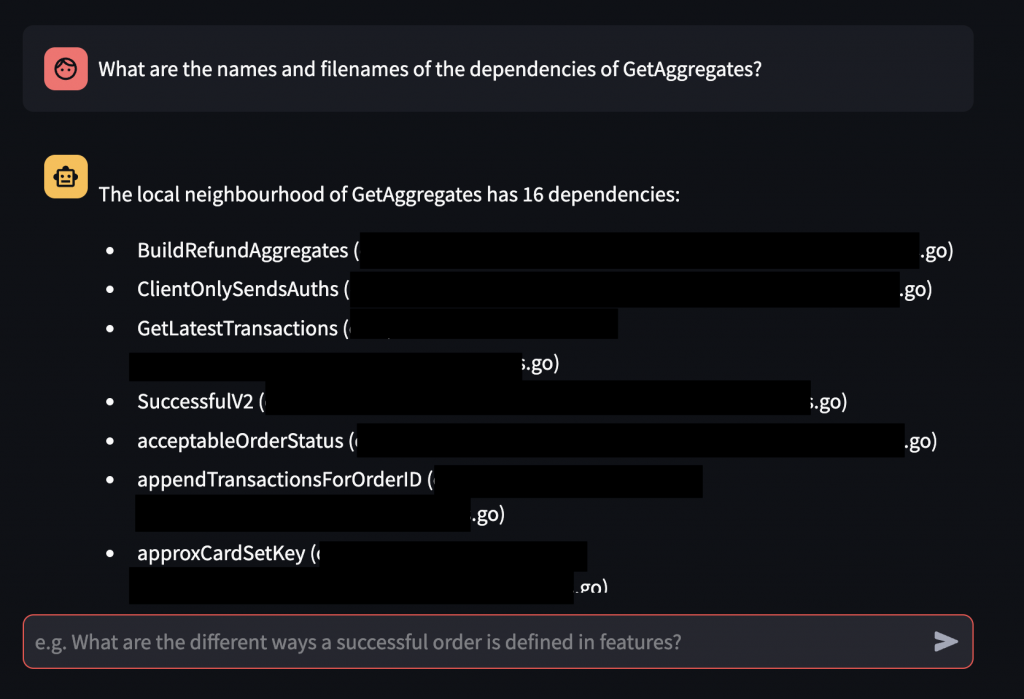

We wrapped it all up into a Streamlit app so that users can have a slick UI, and boom, we have a graph-powered chatbot. Here’s an example of us asking it a question that would only be possible to answer when traversing a graph of code dependencies:

Improvements

The project was a scrappy proof-of-concept that ended up working surprisingly well. While we’ve already addressed some low-hanging fruit, there are additional areas for improvement:

- Microsoft’s graph RAG paper [2] goes into detail about a process where graph communities are identified and summarised hierarchically. These summaries are then used in a multi-step process to construct context windows for the LLM for efficient global query answering. Although we didn’t explore graph communities in our project, this is a promising area for future experimentation.

- We used Gemini as the LLM, as open-source models proved challenging to implement within our timeframe. Future improvements could include fine-tuning an LLM for generating Cypher queries, particularly for use with a Kuzu database.

- Our experimentation with embedding models was fairly limited. A straightforward improvement would be to identify a better embedding model tailored for code-specific question answering.

- Currently, the node index includes only certain nodes (features and core entities). Expanding it to include more node types is an quick way to improve the chatbot’s ability to retrieve relevant starting points for graph traversal, broadening its applicability across the codebase.

Final thoughts

It’s been a very fun project, and the ideas used here are applicable to plenty of other domains. It doesn’t need to be a codebase; you can build a knowledge graph off of any text-based corpus using an LLM, and GraphRAG has been shown to significantly improve LLM performance in these cases [2].

We did actually try chucking our codebase into an LLM and using LlamaIndex’s SchemaLLMPathExtractor with the property graph index to specify the allowed relationships, but we found that our code-analysis derived graph worked best.

References

[1] CodexGraph: Bridging Large Language Models and Code Repositories via Code Graph Databases – https://arxiv.org/pdf/2408.03910

[2] From Local to Global: A Graph RAG Approach to Query-Focused Summarization – https://arxiv.org/pdf/2404.16130